Against the 13F

This past filing season, three fund managers, and their corresponding 13Fs, made headlines: Michael Burry (Scion Asset Management), Leopold Aschenbrenner (Situational Awareness), and Peter Thiel (Thiel Macro). To the payout-maxxing engagement farmer (and, to a lesser extent, the technology-business podcaster), a new 13F is basically a gift from heaven. But for everyone else, they’re misleading at best. At worst, they’re completely useless and a burden on our nation’s glorious capital allocators.

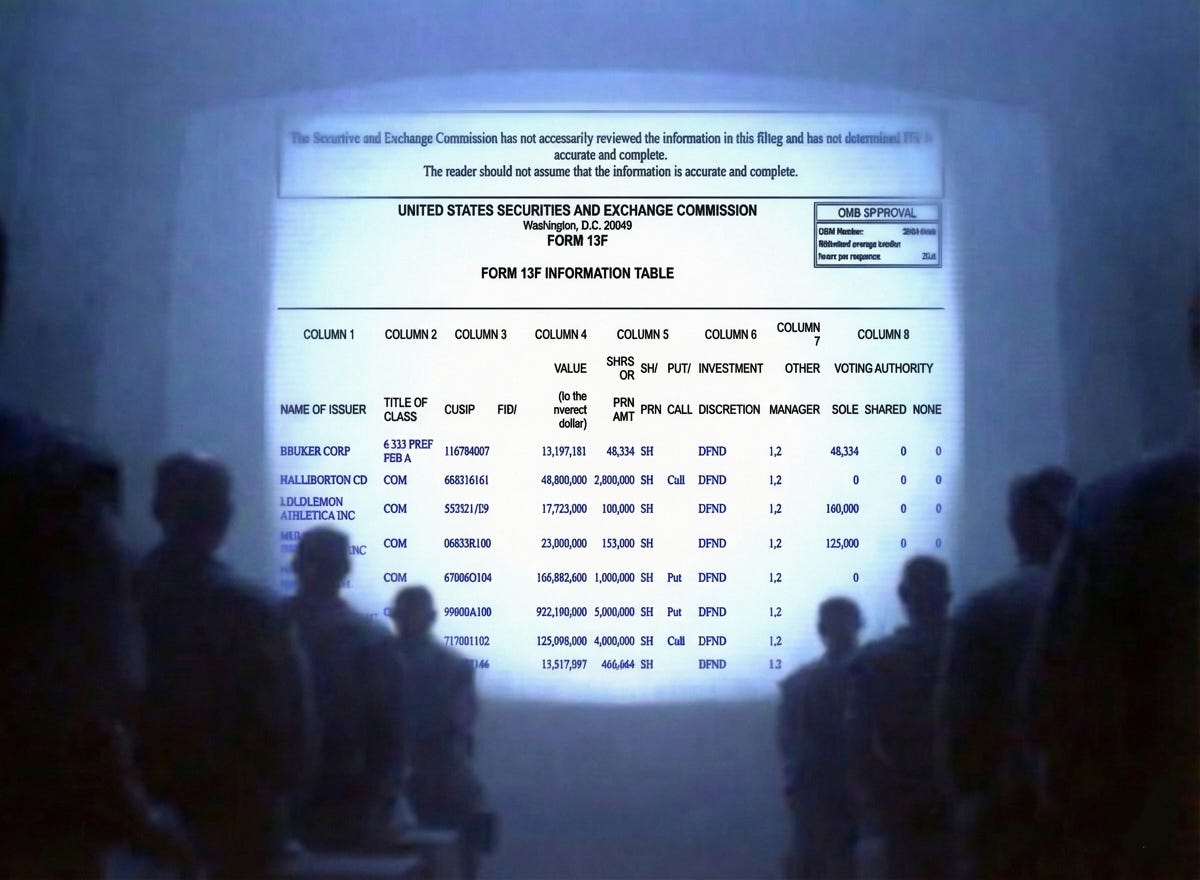

The 13F was introduced by the Securities Acts Amendments of 1975, a set of revisions to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Section 13(f) required managers with over $100m in assets to make periodic reports of their holdings at a granular level: non-exempt securities, aggregate value of exempt securities, voting authority, transaction turnover, and individual trades if large enough. By the time the form was adopted by the SEC in 1978, it had been stripped down to exclude most of the original requirements, with the Commission citing that they would have been excessively complex or unnecessary. It also ignored Congress’ 1934 definition of “exempt securities” and used its own narrower, curated list. What remained was a requirement to report only long positions in U.S. exchange-traded securities (stocks, options, convertible debt, etc.). While great for grabbing attention, the lack of information disclosed can make the form very deceptive.

Let’s start with the Thiel Macro filing. The headline the media ran with was that the fund sold its entire Nvidia stake, likely valued around $100m, which left the 13F quite barren (just $74m split between three equities remains). Conservative estimates put Peter Thiel’s net worth near $25b, meaning the filing would represent about 0.3% of his total wealth. Even assuming that Thiel Macro only manages a small portion of his assets, it’s not clear to me that this is very meaningful if we are trying to gain insight into Thiel’s current economic outlook. For all we know, that Nvidia sale could have been one leg of a pair trade; however, because short positions aren’t reported, we have no visibility into the other side. How is the rest of Thiel Macro invested? Maybe it’s in foreign-listed companies. Or bonds. Or futures contracts. Or real estate. Or maybe he’s just a cash chad. The point is that we have no idea; the 13F doesn’t ask for any of these. And even if you’re convinced that meaningful insights can be drawn from these equity positions, you would be flying blind historically; the fund didn’t even file from 2020 to 2024.

The options positions disclosed on the form are especially misleading. In Scion Asset Management’s filing, Michael Burry made headlines with his $1.1b of Nvidia and Palantir puts. Quite the sum, but it’s important to understand the mechanics of reporting options. On a 13F, the value listed is the notional value, meaning the dollar value of the underlying asset that the option controls. The premium, strike price, and expiration date of the option remain a mystery. The notional value, however, is almost completely useless, because as an option gets further out of the money it gets cheaper while the notional value remains the same. This means that all we really get is the direction of the trade. Burry’s Palantir put contracts, valued at $912m, control five million shares of Palantir. At the time of writing, I can buy Palantir puts expiring at the end of November with a strike price of $131 for $0.459 per share. That means controlling five million shares might cost just ~$2.3m in premium (much less than $912m!). This is an exaggerated example, but from what I see on X it seems many people don’t understand this, despite Burry addressing it. The problem of misleading options valuations can also be seen in the Situational Awareness filing, where $1.9b (~46% of the fund) is in options. Some poasters have taken this to mean that Leopold has more than $4b in AUM. That figure might be true, but you can’t justify it by simply adding together the $2.24b of equities and $1.9b of options that appear on the 13F.

Naturally, one then wonders who benefits from the existence of the 13F, if not the general public. A rival fund could theoretically copy the positions on a 13F if they are inclined to outsource all of their financial research, though they should expect worse returns on average because, from first principles, the overall lack of information and the delay of the filing means that by the time they can actually see the trades, much of the alpha has already gone away. In practice, however, this informational lag is often not strong enough to disincentivize free-riding. And while copy trading may be a theoretically ineffective yet often profitable strategy for that specific fund, the implications of doing so are market-wide. Citadel’s Stephen Berger wrote in April 2022 that “when managers forego independent research and, instead, seek to copy others’ strategies, this leads to herding, which increases volatility.” The publishing fund should also expect to perform worse after it begins filing, a phenomenon shown in the empirical literature. The result is a kind of barbell: the form hurts both top-performing funds and the overall market (from higher volatility and media misinterpretations that distort investor perceptions), while free-riders do fine (the opposite of what we’d ideally want). The market is therefore not generally a benefactor of the 13F, and mandating further disclosures in it would only worsen the negative impacts described above.

Is the SEC the chief benefactor of the form, because it aids in their pursuit of fair and efficient markets? Unfortunately, the answer seems to be no. In a 2010 review, the SEC reported that “despite Congressional intent that the SEC would be expected to make extensive use of the Section 13(f) information for regulatory and oversight purposes, no SEC division or office conducts any regular or systematic review of the data filed on Form 13F.” These filings are so useless that even the regulators don’t look at them.

We’d probably be better off without the filing at all, though I don’t expect its abolition anytime soon. In 2020, the SEC proposed updating the reporting threshold from $100m to $3.5b, which would have tracked the growth in U.S. equities since 1975. According to the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, this would have slashed “the number of reporting filers by 90%, from 5,089 to 550, effectively abolishing Form 13F as a reporting system for most investors.” Unfortunately, due to lobbying efforts from public companies who argued the 13F is important to understand their investor base (despite the existence of the 13D, which outside investors must file when they obtain more than 5% of a company), this proposition never went through and is unlikely to be revived.

While we can hope the 13F someday becomes an obscurity of the past, in the meantime we should make a concerted effort to at least qualify the judgments we draw from them, if not ignore them entirely.

Thanks to John Coogan, Daniel Tenreiro, and Brandon Gorrell for reading drafts of this.

Love this!